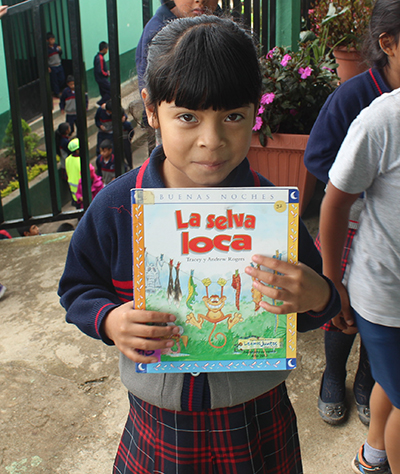

Primary school student in Guatemala.

We celebrate International Literacy Day annually on September 8 to raise awareness of the progress and barriers that surround improving literacy for adults and children. Many educational programs seek to teach children how to read and write in developing nations, but creating programs that actually make a difference is a challenge. That’s why Mathematica is partnering with the U.S. Agency for International Development to implement rigorous evaluations of reading programs in Latin America and the Caribbean through LAC Reads. To mark International Literacy Day 2018, my colleagues Larissa Campuzano, Julieta Lugo-Gil, and Sarah Humpage Liuzzi offered insights about emerging findings from our work with the agency, program implementers, and local research partners in Peru, Guatemala, and Honduras to improve reading outcomes for children from traditionally underserved regions or with diverse linguistic backgrounds in their respective countries.

What are we learning in our LAC Reads research?

Primary school classroom in Peru.

Larissa: In the Amazonian region of Peru, we evaluated Amazonía Lee, a program designed to improve early-grade reading through teacher training. The program is run by local educational authorities with support from a university based in Lima and trains teachers in the best ways to teach students phonics, reading fluency, comprehension, and writing. Teachers also receive in-person coaching to help implement lessons from the training. We found that students from Amazonía Lee schools had better reading outcomes than students in schools that received no additional teacher training beyond that typically provided by local education authorities. However, students in Amazonía Lee schools had similar reading outcomes to students in schools in which another program rolled out by the Ministry of Education, Soporte Pedagogico, provided similar teacher training and coaching to that of Amazonía Lee.

Julieta: In Peru and Guatemala, we evaluated the Leer Juntos, Aprender Juntos program in communities with linguistically diverse populations. Save the Children developed the program based on its Literacy Boost model, which includes teacher training, coaching, and a community involvement component to help students in the Quechua-speaking region of Apurímac in Peru and in the K’iche’-speaking region of Guatemala. We designed the evaluation to assess the impacts of teacher training, coaching, and community involvement components. With regards to teacher training and coaching, we found different results for each country. We found evidence that Leer Juntos, Aprender Juntos teacher training and coaching had favorable impacts on some of the children’s reading outcomes in Peru but not in Guatemala. We did not find evidence of positive impacts of the community action component on reading outcomes in either Peru or in Guatemala.

Do we understand what accounted for the different reading outcomes in Peru and Guatemala?

Julieta: Differences between the study sites in the two countries could help explain the different findings. In both countries, most teachers were observed using Spanish during reading instruction. In some cases, teachers did not have adequate language skills in the students’ mother tongue to deliver the reading instruction strategies taught by the program. In Peru, most students demonstrated proficiency in Spanish early in first grade, and they might have been better able to absorb instruction in Spanish. In contrast, in Guatemala, only about a third of the students entering first grade demonstrated proficiency in Spanish. Regarding the lack of impacts of the community component, relying on volunteer work was problematic in both countries.

What did we learn about improving early-grade reading outcomes in Honduras?

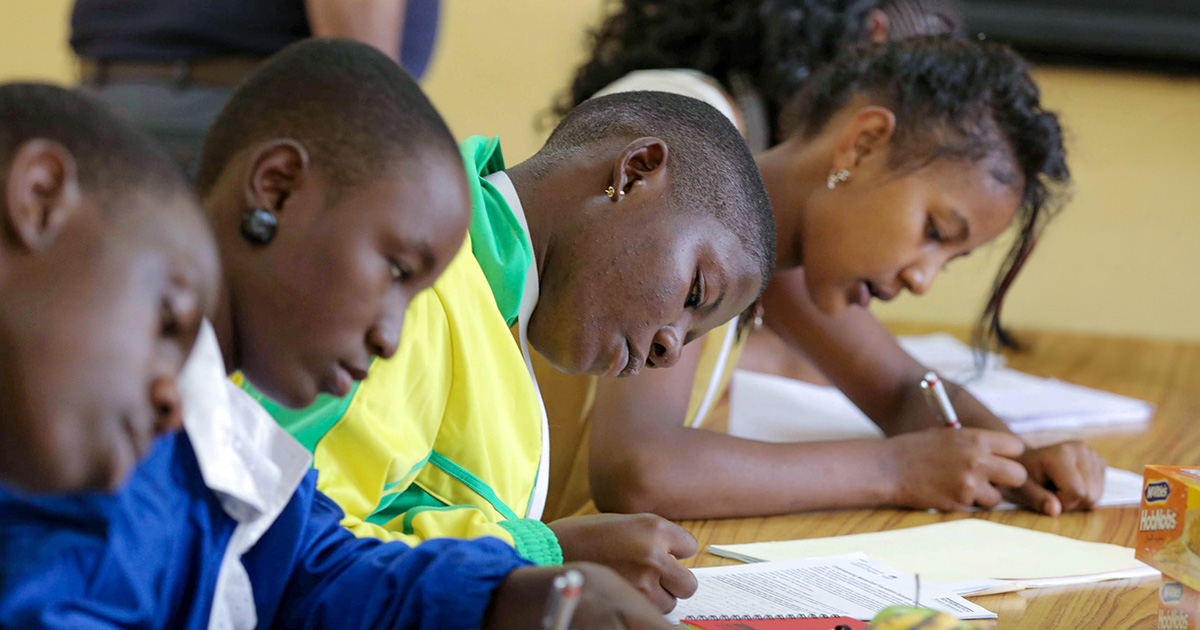

Students in a classroom in Honduras.

Sarah: In Honduras, we evaluated the EducAcción-PRI project, which tested the impact of two types of student assessments on students’ reading skills: end-of-grade summative assessments, designed to measure student learning at the end of each year, and formative assessments, which teachers use to gauge what the students learned and what they might have missed over the past month. Principals and teachers received training and coaching on how to use the results of both types of assessment to focus their efforts on the specific students who needed the most support and on the material that tests revealed was most challenging for students. Principals and teachers used the end-of-grade assessments to help plan for the year, and teachers used the formative assessments to adjust their lesson plans and teaching approach monthly. We found that both types of assessment improved reading test scores overall, but impacts varied between urban and rural schools. The end-of-grade assessments were most effective in urban schools, in which principals managing large student populations might have benefited more from the test score data. The formative assessments had the largest impact in rural schools, in which teachers—less experienced on average than their urban counterparts—might have benefited most from the additional support.

Can we conclude that teacher training and coaching is a promising approach to improve students’ reading outcomes?

Primary school classroom in Honduras.

Sarah: It is important to recognize that there is not a one‑size-fits-all approach to improving educational outcomes. Teachers, their training and support, instructional practice, language of instruction, and other factors influence how a child learns to read. A program that worked really well in one country or for one age group might not work in another country or with a different age group. Nevertheless, teacher training programs show a lot of promise.

Larissa: Another important factor is the scale of implementation. The studies of teacher training programs we described here were implemented regionally, and although we found that in some contexts the programs work, implementing these programs at a larger scale would pose more challenges. Program implementers would have to make sure that available resources exist to be able to implement the program at a larger scale and with fidelity. If the program must be modified to be launched at scale, we should not expect the same results as in the small‑scale studies.

You can learn more about how Mathematica is helping our partners uncover evidence to improve educational outcomes in developing nations on our education page.